Apologies and Other Regrets

James T. Hong

Empty Gallery is pleased to present Apologies and Other Regrets, James T. Hong’s second solo exhibition with the gallery. Since the late 1990s, Hong has produced searing moving image works which deploy elements of experimental, documentary, and essayistic filmmaking to critically address issues of class, race, and historical trauma in America and East Asia. His research-based practice often operates along the fraught intersection of epistemological and socio-political questions, interrogating the manner in which knowledge is produced, disseminated, and manipulated in the service of power.

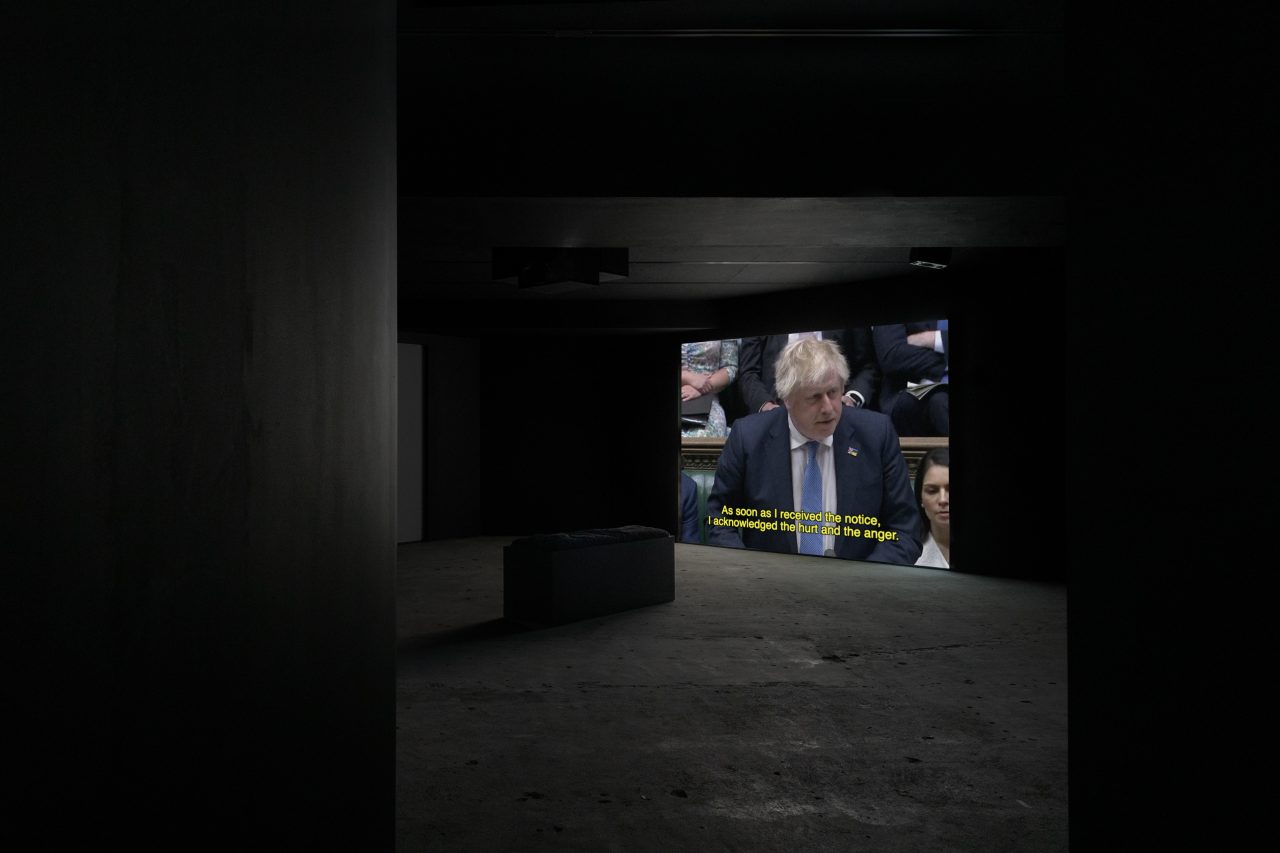

In our 19th floor gallery, Hong presents the newest iteration of his film Apologies (2012-ongoing) in a monumental three-channel version. Shown most recently at the Jewish Museum in Vienna, Apologies is a taxonomic investigation into that most contemporary phenomenon: the political apology. Hong’s film functions simultaneously as documentation of the technics of mediatized diplomacy, and a sort of historical index of past atrocities via their—often facile—national acknowledgements. Painstakingly assembling broadcast footage of various heads of state— from Willy Brandt’s historic visit to the Warsaw Ghetto to contemporary regrets over the seizure of indigenous land—Apologies sometimes resembles a perverse compilation of “greatest hits”, albeit one filtered through Hong’s uniquely grim sense of humor and the rhythmic seriality of the structural film. Apologies may at first seem impenetrable, or perhaps even arbitrary, a procedural exercise whose aura of gray facticity and strained propriety contains few aesthetic charms. But after a while, the polished surfaces of these diplomatic performances start to exert their own sort of hypnotic pull. Within the overdetermined space of the public apology, attention is drawn towards the supposedly inessential. The viewer watches for inevitable fissures between script and performance, moments of either semiotic scarcity or excess, analyzing the politician’s body like a text, on the hunt for insincerity or double-meanings communicated through the length of a pause or tilt of the head. Experiencing these performances in series, one is occasionally struck by a strange sense of pathos. However terrible the leader or great the crime, we are still confronted with the insufficiency of a single human body to ever contain the symbolic weight of history and nation—perhaps pointing to the essential futility of even apologizing for these events at all. Apologies, then, proffers itself as evidence of the failure of modern politics to address historical trauma and break free from cyclical violence—the supposed moral progress of history reduced to a formalist repetition of apologetic styles.

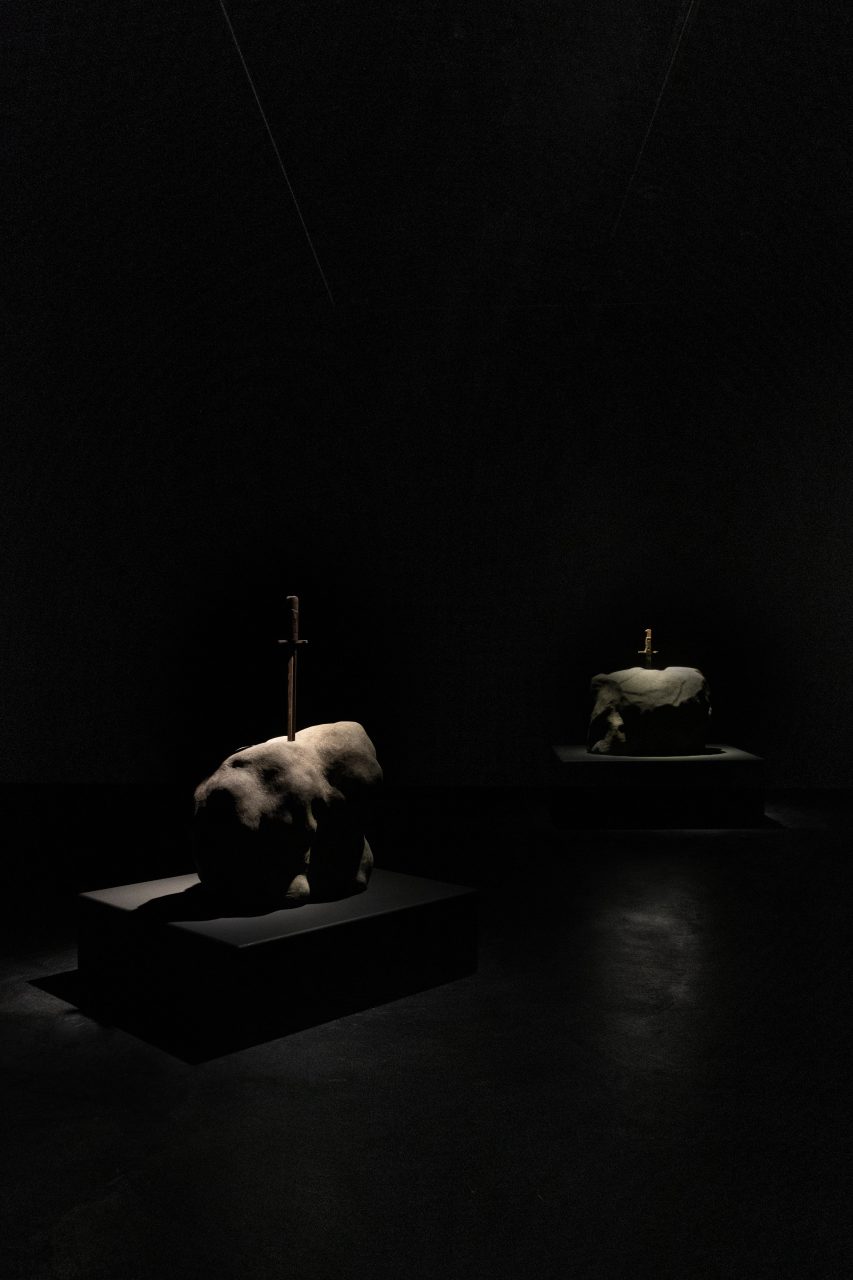

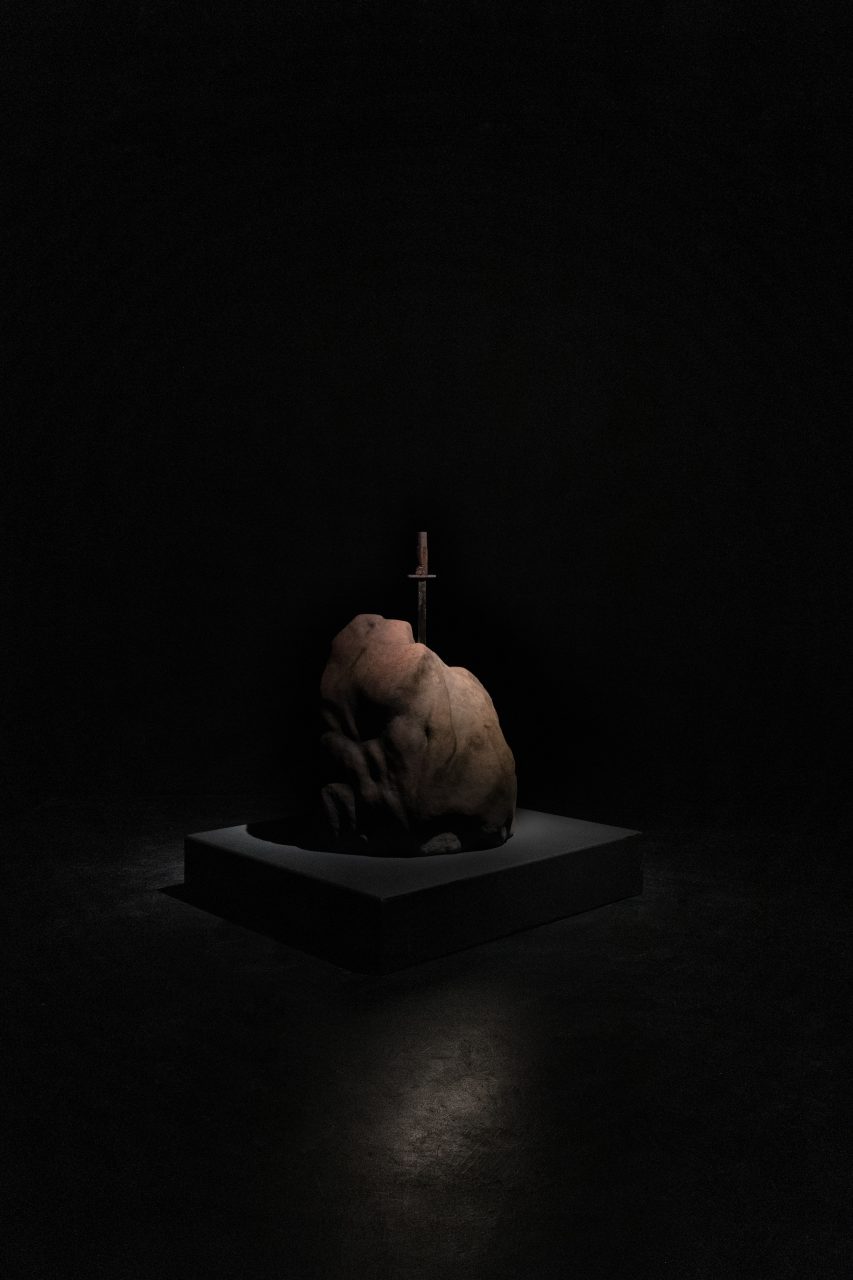

On our lower floor, Hong will also present a series of new sculptures entitled Stabbed In The Back. Referencing the famous English fable of the sword in the stone, these sculptures take the form of trompe-loeil rocks––resembling what one might find on a film set or amusement park— embedded with WWII-era Japanese bayonets. Juxtaposing the light-hearted kitsch of the fantasy prop with the brutal facticity of the murder weapon, these works point to the complex dialectic between historical truth and national mythology. Embodying the (literal) weaponization of trauma, they bear witness to the ever-present possibility for real historical violence to re- animate itself and erupt into the present.

Apologies and Other Regrets

I Absolute sovereignty

The English term ‘sovereign’ derives from the Latin roots super (‘above’) and regnum (‘kingdom’). It refers to a supreme ruler (often a monarch), and extends to the related concept of sovereignty—the authority to govern oneself and others absolutely. This is where things start to become tricky, because no matter how hard you look, there is no way to guarantee this power over oneself and others—a major bummer for rulers, who must constantly refresh and reinforce the terms of any claim to power. In most modern states, political legitimacy is neatly folded into a machine for organising competing interests through the transparency of law, the accumulation of capital, or the use of military force. But something about this machine is always leaky, always venting air, always vulnerable. The concept of sovereignty itself seems to suggest something deeper and more fundamental than any machine at all: something intractably organic, cosmic or absolute. This inherent deficit leaves modern states and modern subjects always yearning for the mythical closure of an absolute claim, for the unity and totality that the circular, transactional logic of administrative power can never provide. From this perspective, sovereignty can only ever be experienced as a painful split—a necessity to decide one’s own fate, but also a failure to secure any significant guarantees for doing so against constant challenges. And the remedies are always colourful and clever—absolute right can spring out of anything from God’s lightning bolts, family bloodlines, to supernatural claims to superpowers and contact with aliens. To be truly proud and truly whole by reclaiming what has been revoked since our mythical origin, another desperate solution is to simply vanquish our enemies—who are often our weakest and most defenceless neighbours.

II HARM

It can be hard to understand how a government can order a full-scale genocide, whether in a neighbouring country, an occupied territory, or within its own dominion. It can be hard to understand how such violence can receive the full support of a nation’s people. It can be hard to understand while it is happening to you, and it can be hard to understand while you are fully supporting it. Just as it can be hard to understand how it happened in the past, repeatedly, and often under the auspices of modern territorial, industrial, or political progress. On the other hand, there are times when, at the highest levels of power, a government must publicly recognize that harm has been done, whether out of genuine remorse or fear of reprisal, by issuing an official apology. And yet, time cannot move backwards to undo what has already taken place. No one can bring back the dead from a massacre or a genocide. But if that is the case, why bother apologising at all?

III APOLOGIES

James T. Hong’s video installation Apologies (2012-ongoing) is a compilation of modern political apologies. In Hong’s own words, Apologies is “a timeline of modern political progress as unrepentant recidivism and contrite repetition”. As a work-in-progress now approaching seven hours in length, it continues to grow, absorbing further documentation of political regrets each year, according to the rule that any apology be issued directly from the seat of power—not, for example, by a retired member of state or as an expression of personal sentiment. They must be formal, official declarations of the highest order. Which does not mean that all are successful, or even convincingly apologetic. On the contrary. Still, within the exceptional interval of the political apology, a technically sincere expression of feeling eclipses the practice of power and the modern nation state can become a strange foreign object. In the case of Apologies, this strangeness extends to a broader civic apparatus where gestures of goodwill shrivel in the face of irrevocable error and the irreversibility of time. The fiction of sovereignty pertains not only to state power, but also to what we can expect from one another.

Watching repentant heads of state leads one to wonder how such a gesture could be received by those for whom it should be most meaningful. Has the adequate dosage of sincerity been administered in the performance? If not, what does it expose about the intentions behind the original harm? Will the apology even fulfil any political purpose at all?

IV BLOWBACK

In the unstable interval of the apology, there are also significant risks. Feelings and sensitivities can run wild with rogue interpretations. A shortfall of remorse may reveal a latent intention to repeat the regrettable act. The supposed progress ofIn letting bygones be bygones, supposed progress may cause everything to snap back to the very beginning of the trauma, reopening wounds that had to some extent healed with the passing of time. The perpetrators, still thinking themselves gods, may believe their acknowledgement and supplication to have great value. In fact, their apology creates an abysmal mirror that refracts and further extends the offence, now destined to play on loop for eternity. No matter how necessary or sincere, the apology’s futile symbolism can always backfire—especially when addressing immense pain that future generations will inherit. And yet, the nature and extent of the harm holds great power over what the apology can achieve. Symbolic harm, like a clumsy insult, can usually be erased by the symbolic balm of an apology. Sorry! I take it back! I didn’t mean it! But what if the harm caused irrevocable damage? What if the same government that ordered an ethnic cleansing, a full-scale extermination filled with spite and malice, absent of all feeling or compassion, must apologise? It can only do so by fabricating such an overabundance of feeling and compassion that it might neutralise the effects of its damage—and still without restoring anything that was lost.

A more profound and painful process of self-examination comes when, in full shame, a perpetrator contends with their own power to kill and maim, measuring their own identification with their deeds. If some self-denigration or submission to the unfathomable, some product of humiliation, can be extracted from the act of performing an impossible task, this just might work. But such a wrenching self-examination, however sincere, never really happens, because being a perpetrator is only a matter of perspective. Nations often play the role only temporarily, and for rhetorical reasons. A number of entries in Apologies follow military defeats, making the acknowledgements necessary pragmatic moves for removing paralysing constraints on continued sovereignty. The acknowledgements of atrocities committed by victors of the same conflicts, on the other hand, are consistently absent from the work, because those acknowledgements never took place. Victory justifies atrocity retroactively, and who really apologises for winning?

A well-delivered apology might soothe pain that would otherwise have grown to monstrous proportions, causing damage to the state and to the highest levels of power. A well-delivered apology understands that revenge can taste delightful, and that retaliatory violence can easily surpass any original transgression, especially when delivered under the cover of unacknowledged pain. Especially when it seeks a pyromaniac reckoning, a total undressing of all historical power.

V Excalibur

James T. Hong’s Stabbed in the Back (2023-ongoing) is a series of sculptures featuring an authentic Japanese bayonet used in the Second Sino-Japanese War (instigated by the Empire of Japan on the Republic of China from 1937–45) embedded in a mock stone made of plastic and styrofoam. At first the scene might appear funny, because many are familiar with the legend of Excalibur, the sword in the stone that young Arthur, unaware of his birthright and lineage, extracted to reveal himself as the “one true king” of Britain. This is the special alchemy of sovereignty par excellence: a blood anointment tinctured with the innocent heart of good moral character, a totem of power as a riddle in matter. It is the supernatural predestination that haunts sovereign power, a yearning for a legitimacy so real that it can only exist as fiction.Instead of harbouring Excalibur’s magical legitimacy, Hong’s stone is penetrated by an actual weapon of Imperial Japan, whose influence by European imperialism and fascism is well known. Returning the Japanese bayonet to the Arthurian legend of British sovereignty popularised by Disney’s 1963 animated film creates an uncanny familiarity, even if by criss-crossing divergent cultural and political histories. The bayonets used in these sculptures were bought from collectors of Sino-Japanese War memorabilia or elderly former soldiers of Imperial Japan. Indeed, the Empire of Japan’s bloodthirsty conquest of China left millions dead, as Japanese prime minister Tomiichi Murayama first acknowledged in a famous 1995 statement included in Hong’s Apologies. These blades, in stark contrast with the set-designed rocks which hold them, may well have shed blood or taken Chinese lives in their time—making them prime material for a later wave of ascendant nationalism drawing from shared trauma and victimhood. Sheathing them now in a British magical legitimacy made of plastic and foam might seem cheeky. And yet, a time may come when the material reality of the blade converges with the consequences of impossible sovereignty, because the sword in the stone can only await the arrival of a rightful heir who can claim its power once again.

VI Enemy inside

Real national repentance is unfathomable when some part of the perpetrator also understands himself to be the victim, or as having been forced by circumstances outside of his good nature into monstrous deeds. Furthermore, severe humiliation initiates yet another catastrophic sequence. A perpetrator may appear pragmatic and apologetic, but may also commit the same atrocity again, and apologise again for that. A perpetrator may sleep, like a sword in a stone, rebranding its cities as hubs for creatives and young entrepreneurs, all the while awaiting the right moment to strike once more. The quest for sovereignty is ultimately self-consuming, whether in its cyclical smoothness or its contorted, fumbling desperation. There are many techniques of occupation and many popular formulas for legitimising dominion over others, but how far can they go when absolute control over oneself—whether as a political body or organism—can never be total? In the end, the perpetrator can only misrecognise himself, turning inward against his own body like a cancer.

—Brian Kuan Wood

Apologies, James T. Hong at Empty Gallery, H.G. Masters, ArtAsiaPacific

Apologies and Other Regrets, Chris Wan Feng, Ocula

Interview with James T. Hong, Shuman Wang, Artforum China

From the Pope to Macron, world leaders’ apologies compiled for artist’s Hong Kong show, Mabel Lui, South China Morning Post