Vanishing in the Wilderness

Yutaka Matsuzawa

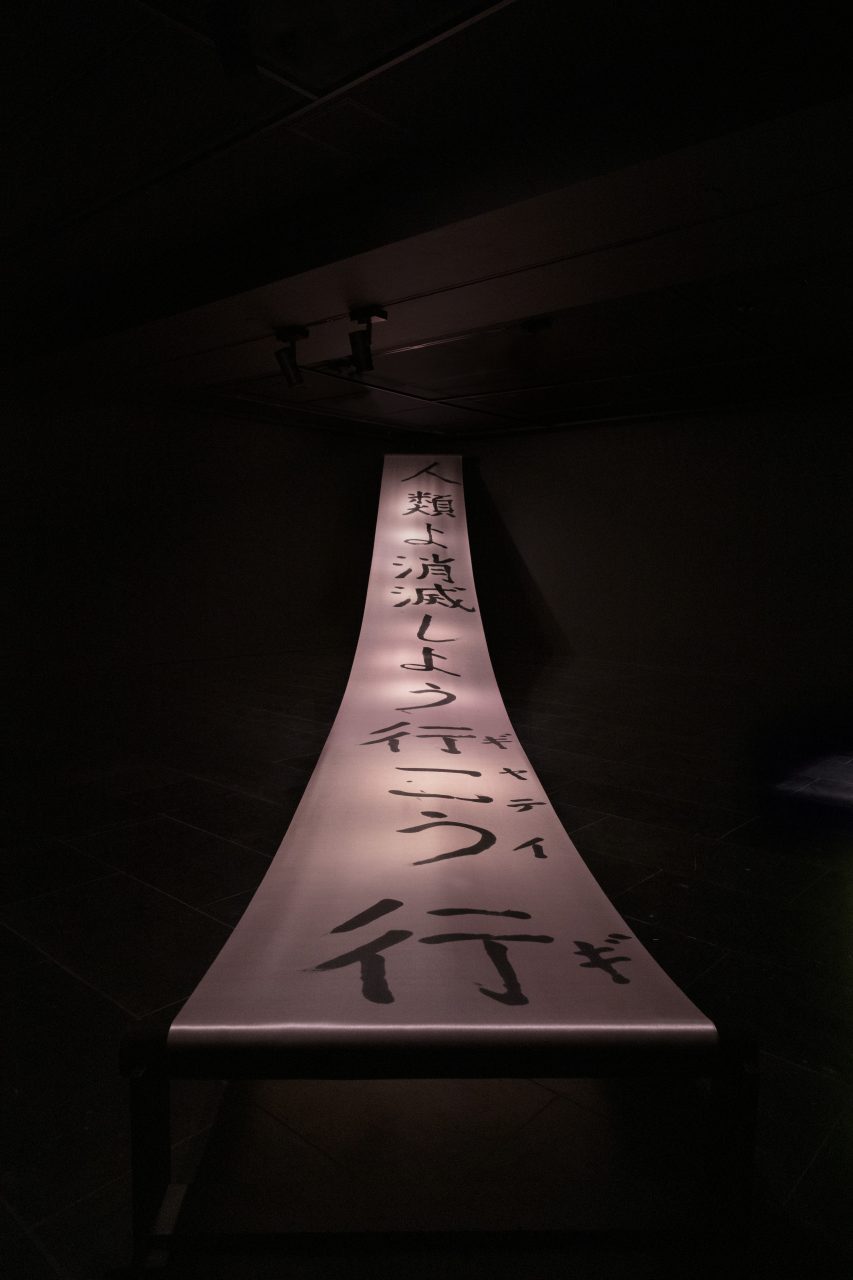

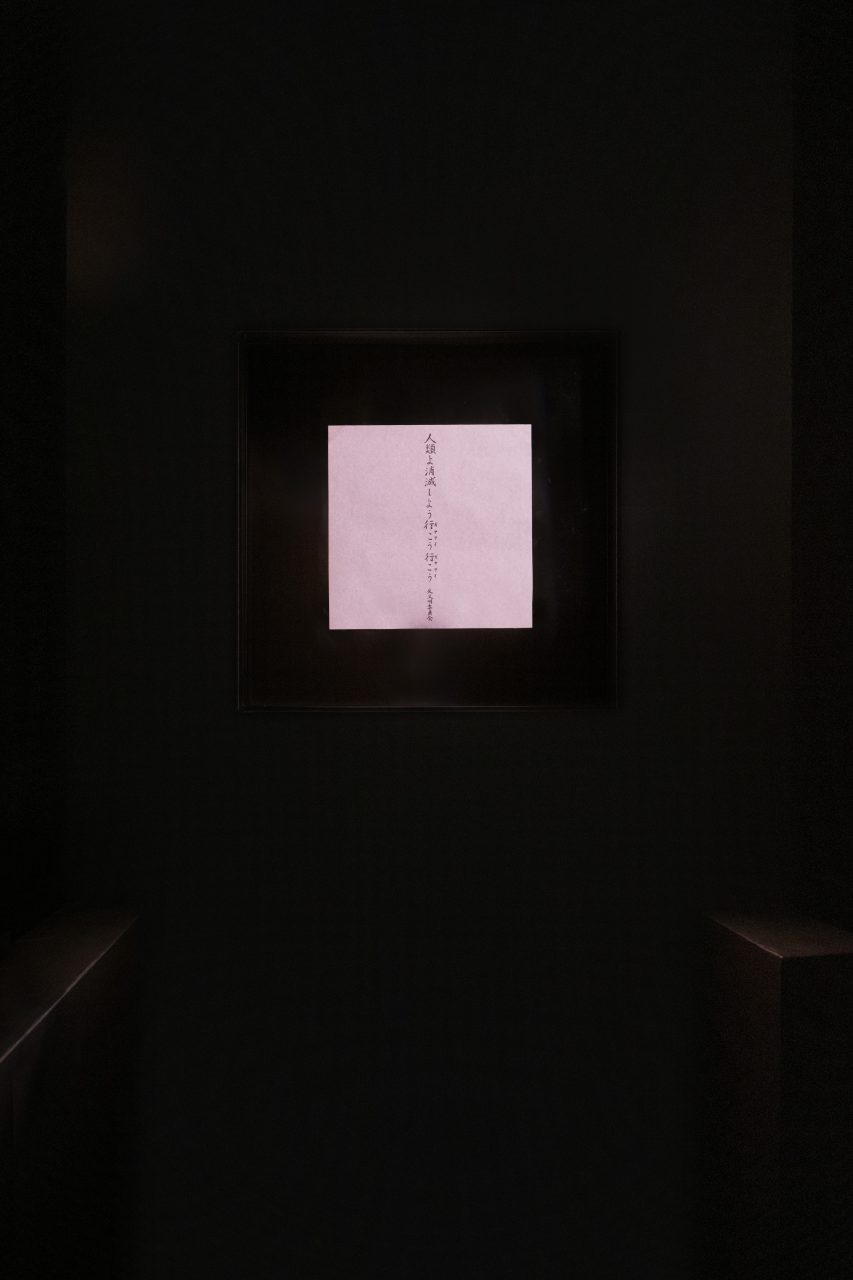

Yutaka Matsuzawa, Banner of Vanishing (Humans, Let’s Vanish, Let’s Go, Let’s Go, Gate, Gate, Anti-Civilization Committee), 1966/2016. Silkscreen on fabric (replica).

Courtesy of Matsuzawa Kumiko and Empty Gallery

Photo: Michael Yu

Yutaka Matsuzawa, Banner of Vanishing (Humans, Let’s Vanish, Let’s Go, Let’s Go, Gate, Gate, Anti-Civilization Committee), 1966/2016. Silkscreen on fabric (replica).

Courtesy of Matsuzawa Kumiko and Empty Gallery

Photo: Michael Yu

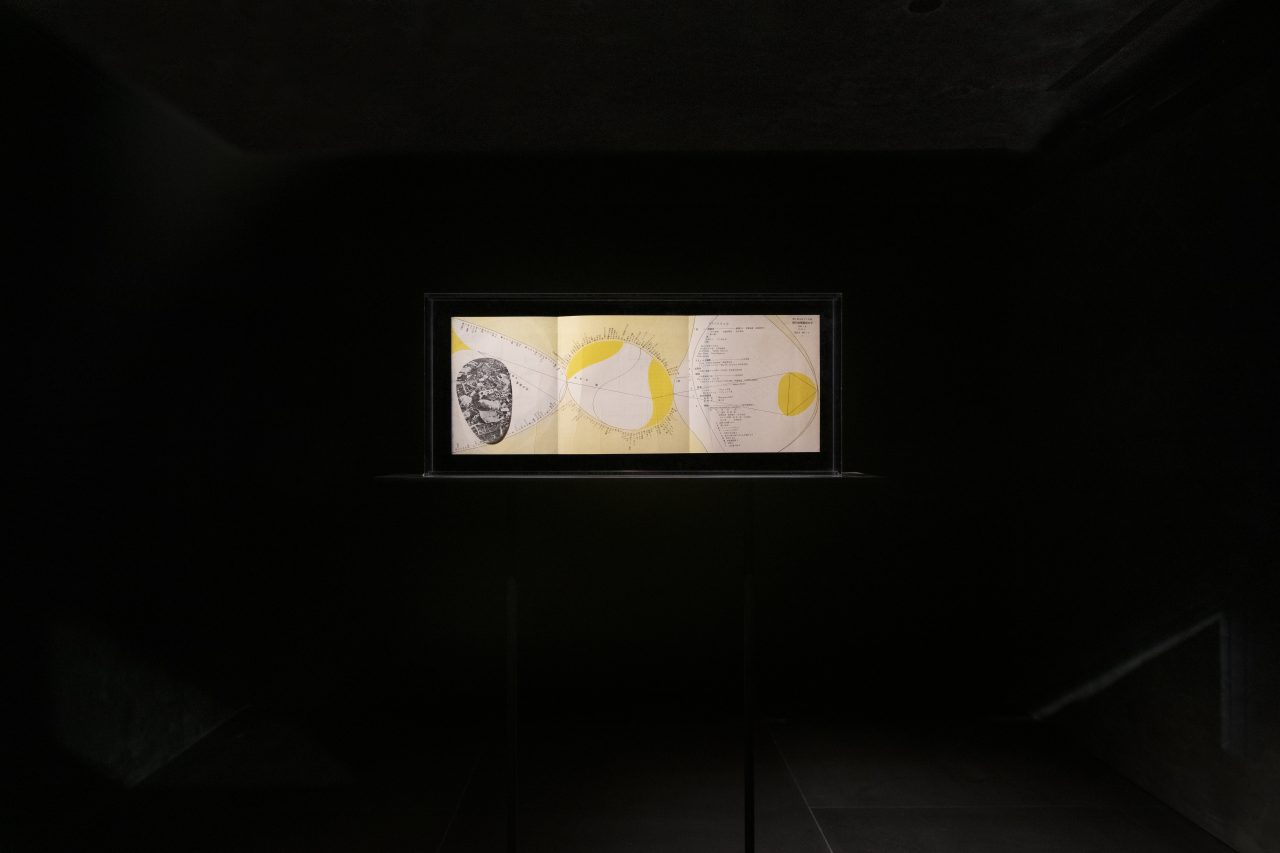

Yutaka Matsuzawa, Rati, no. 1, 1951. Printed matter (brochure).

Courtesy of Matsuzawa Kumiko and Empty Gallery

Photo: Michael Yu

Yutaka Matsuzawa, Rati, no. 1, 1951. Printed matter (brochure).

Courtesy of Matsuzawa Kumiko and Empty Gallery

Photo: Michael Yu

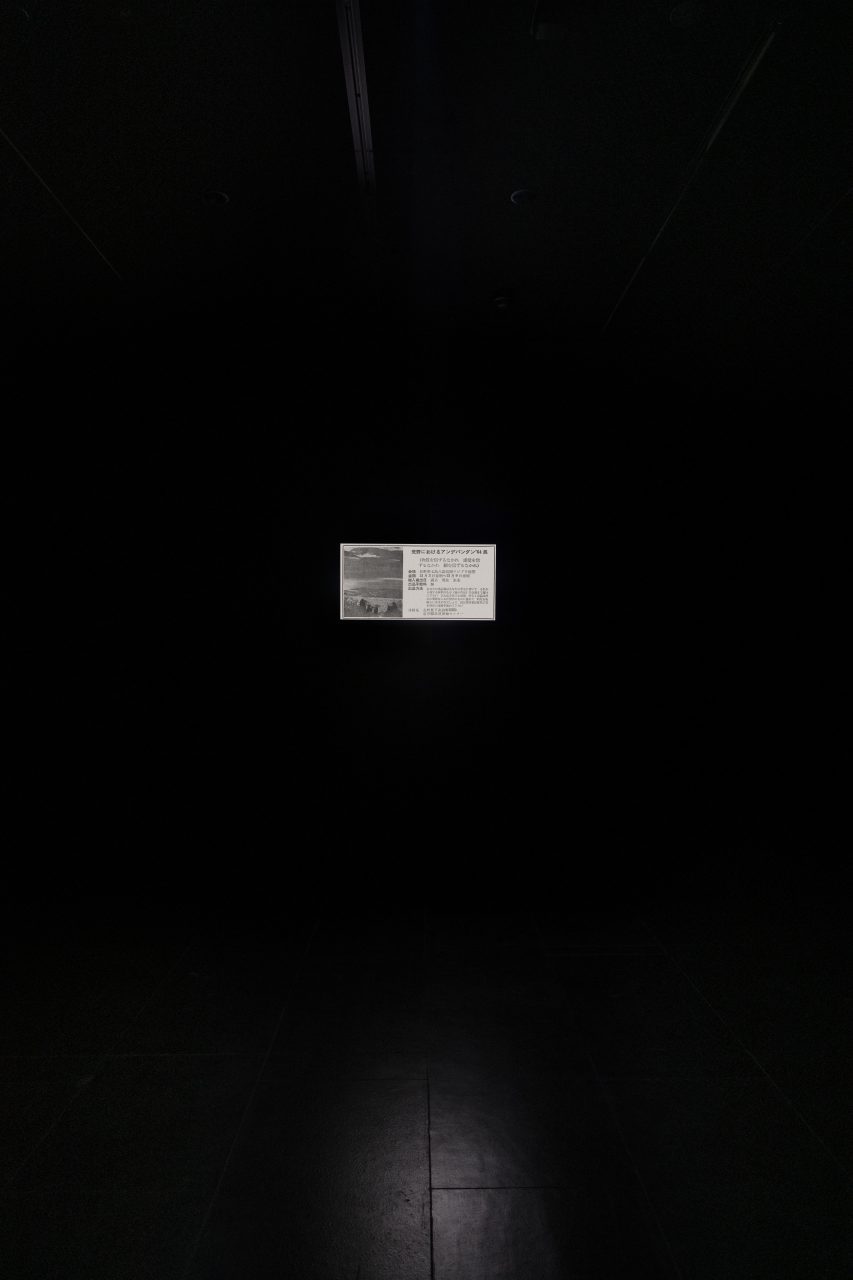

Yutaka Matsuzawa, Independent ’64 in the Wilderness, 1964. Magazine ad, published in Bijutsu jānaru (October 1964): 51.

Courtesy of Matsuzawa Kumiko and Empty Gallery

Photo: Michael Yu

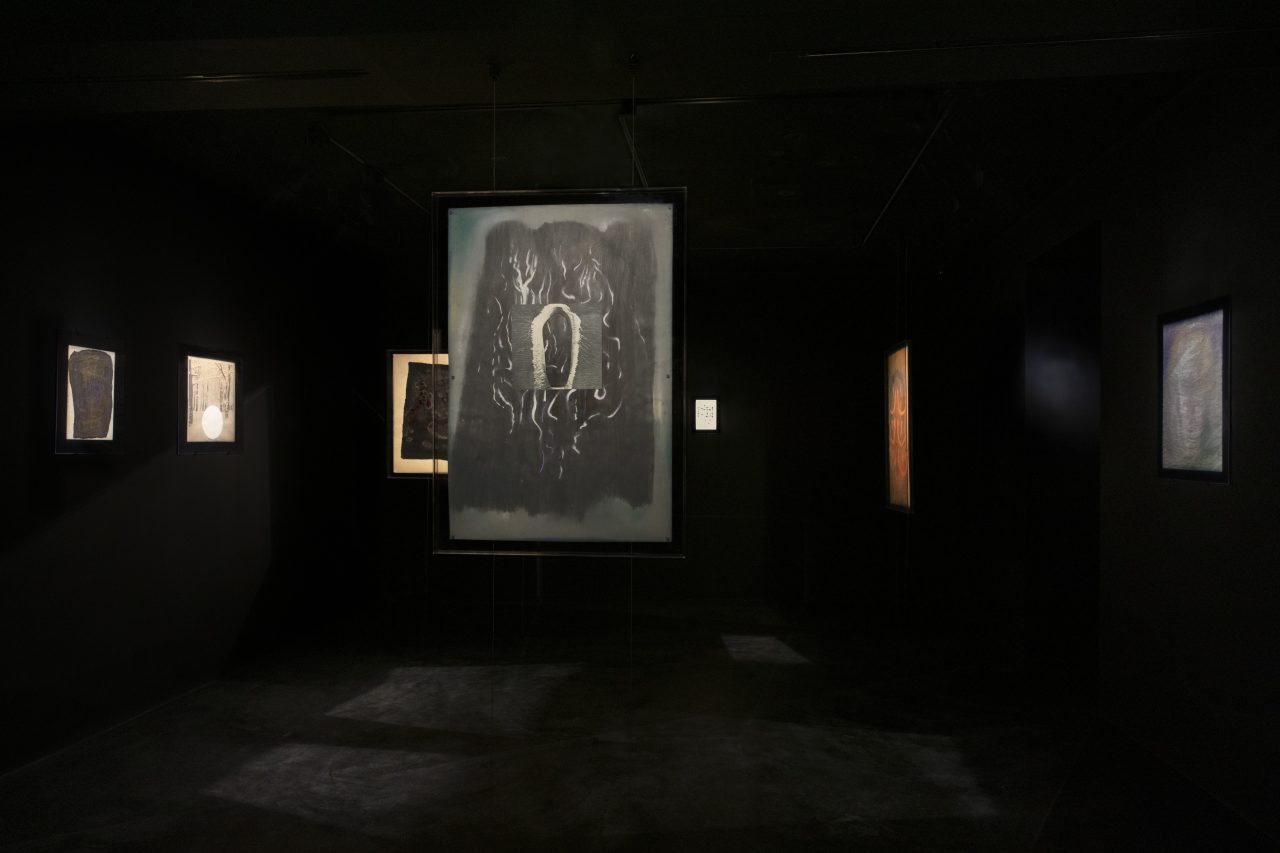

Installation view of Yutaka Matsuzawa: Vanishing in the Wilderness.

Courtesy of Matsuzawa Kumiko and Empty Gallery

Photo: Michael Yu

Installation view of Yutaka Matsuzawa: Vanishing in the Wilderness.

Courtesy of Matsuzawa Kumiko and Empty Gallery

Photo: Michael Yu

Installation view of Yutaka Matsuzawa: Vanishing in the Wilderness.

Courtesy of Matsuzawa Kumiko and Empty Gallery

Photo: Michael Yu

Installation view of Yutaka Matsuzawa: Vanishing in the Wilderness.

Courtesy of Matsuzawa Kumiko and Empty Gallery

Photo: Michael Yu

Installation view of Yutaka Matsuzawa: Vanishing in the Wilderness.

Courtesy of Matsuzawa Kumiko and Empty Gallery

Photo: Michael Yu

I don’t, in fact, write for the dead, but for the living—though of course

for those who know that the dead too exist.

Paul Celan, Microliths, They Are Little Stones, 1969

Empty Gallery is pleased to present Yutaka Matsuzawa: Vanishing in the Wilderness. Co-curated by Alan Longino and Reiko Tomii, and realized with the generous assistance of the Matsuzawa family, this exhibition represents the first overview of this pivotal artist’s practice in Sinophone East Asia. Widely considered the leading pioneer of Japanese conceptual art, Matsuzawa’s practice synthesized a diverse array of Eastern and Western knowledge— including parapsychology, Pure Land Buddhism, quantum physics— in the pursuit of artistic strategies for expressing the immaterial sphere. Split like an atom between the gallery’s two levels —generative both separately and together—the 19th floor features canonical works from Matsuzawa’s post-revelation period, while the 18th floor presents earlier paintings and collages spanning the mid 1950s through the early 1960s— works which have rarely been shown outside of Japan.

This exhibition begins with a call for proposals from 1964. Calling for artists to exhibit their work with Matsuzawa in the highlands of central Japan, three aphoristic directions instructed would-be participants:

Don’t Believe Matter

Don’t Believe Mind

Don’t Believe Senses

As instructions, they are formally conscious of the dominant Conceptual art being practiced globally at the time. However, as poetry, they conjure a speculative world that helps the individual temporarily return to a world of dissolution and disappearance.

Vanishing, disappearing, dropping out. In the 1950s and 60s, many artists were experimenting with these concepts. Burning and destroying works, or wholly removing themselves from the art world as they saw it, their activities nevertheless left traces through which we can reconstruct these techniques of disappearance. However, Matsuzawa, individually and in association with his colleagues, forged a path that was at once more internal and less demonstrative than those of his international peers. This path moved beyond the simple physical removal of the artist’s body or artwork to embrace the conscious disintegration of the perceiving individual. This removal is illustrated best by co-curator, Reiko Tomii, who notes that the concept of “being in the wilderness,” or zaiya, is similar to the Chinese xiaye (下野), literally meaning to “descend to the wilderness” and historically denoting a “departure from state power.” Matsuzawa firmly rooted his radical conceptual art practice in this wilderness, which he frames as a place where the presence of living beings and ancestors is deeply intertwined.

In this exhibition at Empty Gallery, Matsuzawa’s Banner of Vanishing (1964) occupies a position of central importance. The message in the banner appears simple enough, proclaiming: Humans, Let’s Vanish, Let’s Go, Let’s Go, Gate, Gate — Anti-Civilization Committee. It asks the visitor to accompany the artist in moving beyond a world based on matter, and in doing so, to pursue an alternative to material civilization. While the language of the banner can be read superficially as pessimistic or nihilistic, Matsuzawa’s intentions were in fact the opposite. Rather than focusing on the surface language that Matsuzawa employed, it is necessary to focus on a physical quality of the work that he considered immaterial in nature. Specifically, his use of pink. In Matsuzawa’s vision, pink came to symbolize the presence of the spiritual. Less a color and more a form, the occasional yet conscious deployment of pink in his oeuvre was part of a strategy to enable the viewer to access the immaterial world in its most invisible nature.

Notes on Pink:

1. In the pink of oblivion there must be innumerable seasons, each both more and less factual than the one before it.

2. A pink result was found as the oldest color on record, at over 1.1 billion years old. The oceans, which contained photosynthetic organisms that produced this colored chlorophyll, might even have once been colored pink. As one co-author of the report commented, it was “truly an alien world.”

Matsuzawa’s work might be imagined as a remnant of this alien, future-past world. Its memory tinted pink from the world it came from, and an image for what worlds may come. A meditative exercise by the artist titled, White Infinity 1 (1967), asks the participant to experience within one’s consciousness an infinite expansion of white paper in a two-dimensional fashion. The Banner of Vanishing might be seen as extending a similar concept––the emptiness that it aspires towards ultimately allowing even the gallery to vanish and disappear. Existing in total darkness, the threads of the work’s future unravelling found frozen in space with the world having since disappeared.

On the 18th floor Matsuzawa’s earlier works are arranged as processional bodies, where proverbs and parables may arrive to the visitor. Abstract in form and often incorporating elements of collage, they are worked over in oil, pastel, self-mixed pigments, and ink. Notably more colorful and expressive than the post-1964 works which Matsuzawa became most well-known for, they were completed at a time in art history when, under increasing ideological pressure, Abstract Expressionism was beginning to fossilize into Minimalist painting. Lee Krasner, recognized as one of the leading critics and practitioners of Abstract Expressionism, stated:

the attempt at purity of a [Abstract art] work is alarming. It terrifies me in a sense. It’s rigid, as against being alive.

These experimental works did not aim towards any sense of formal purity, they instead partook of a form of art that asked artists only to “splash about from the wine of one’s heart.” This phrase, adopted from the early ink paintings of Sesshū, asks artists to not aim towards refinement, but instead to live and create—drunkenly and openly—in the dazzle of the heart’s openness. With the whole of art history under review, they did not adhere to any particular genre or movement. Instead Matsuzawa sought to construct a new system of belief. Though they diverge aesthetically from the conceptual attitudes of his later works, they reflect the same metaphysical engagement with the myriad worlds lying beyond our material plane. Matsuzawa’s practice does not hinge upon art as emotional conveyance, but rather upon the belief that art may foment new trajectories and parameters for sensing what worlds exist elsewhere.

Matsuzawa would often speak of a shift happening within his artworks—like a momentary ripple in the fabric of sober consensus reality. Like the exhibition, which moves back in time to Matsuzawa’s beginnings, this text also looks back.

Slipping backwards, through the membrane of closed eyes, as pink moments drift silently in the dark, a fetal caress echoing from a prior mother and a spirit which whispers on air: let’s go.

Text by Alan Longino

Yutaka Matsuzawa (1922-2006) is considered a pioneer of Japanese conceptual art. Born in Shimo Suwa in central Japan, he studied architecture during the war and upon witnessing the after effects of the firebombing of Tokyo in March 1945, he proclaimed upon his graduation from school that he wished “to create an architecture of invisibility.” After giving up his architectural practice, he wrote poetry, made paintings, and worked as both an artist and teacher in his hometown. In the formulation of his practice, Matsuzawa began to develop a unique understanding of conceptual art that both elevated and transcended the typical notions of conceptual art in the Western, Euro-centric art worlds.

Alan Longino is a Ph.D. student in art history at the University of Chicago. His work focuses on artists of East Asia as well as the Southern U.S. An on-going project of his considers the presence of telepathy within information as a source of image production. His writing has appeared in Heichi and the Haunt Journal of Art, from UC Irvine.

Reiko Tomii is an independent art historian and curator, who investigates post-1945 Japanese art which constitutes a vital part in world art history of modernisms. Her early works include her contribution to Global Conceptualism (Queens Museum of Art, 1999), Century City (Tate Modern, 2001), and Art, Anti-Art, Non-Art (Getty Research Institute, 2007). She is co-director of PoNJA-GenKon, a listserv group of specialists interested in contemporary Japanese art. With PoNJA-GenKon, she has organized a number of symposiums and panels in collaboration with Yale University, Getty Research Institute, and other major academic institutions. Her recent publication is Radicalism in the Wilderness: International Contemporaneity and 1960s Art in Japan (MIT Press, 2016) received the 2017 Robert Motherwell Book Award. In 2019, based on the book, she curated Radicalism in the Wilderness: Japanese Artists in the Global 1960s, which included a major section on Matsuzawa Yutaka, at Japan Society Gallery in New York. In 2020, she received the Commissioner for Cultural Affairs Award from the Japanese government for cultural transmission and international exchange through postwar Japanese art history.