The Garden of Loved Ones

Richard Hawkins

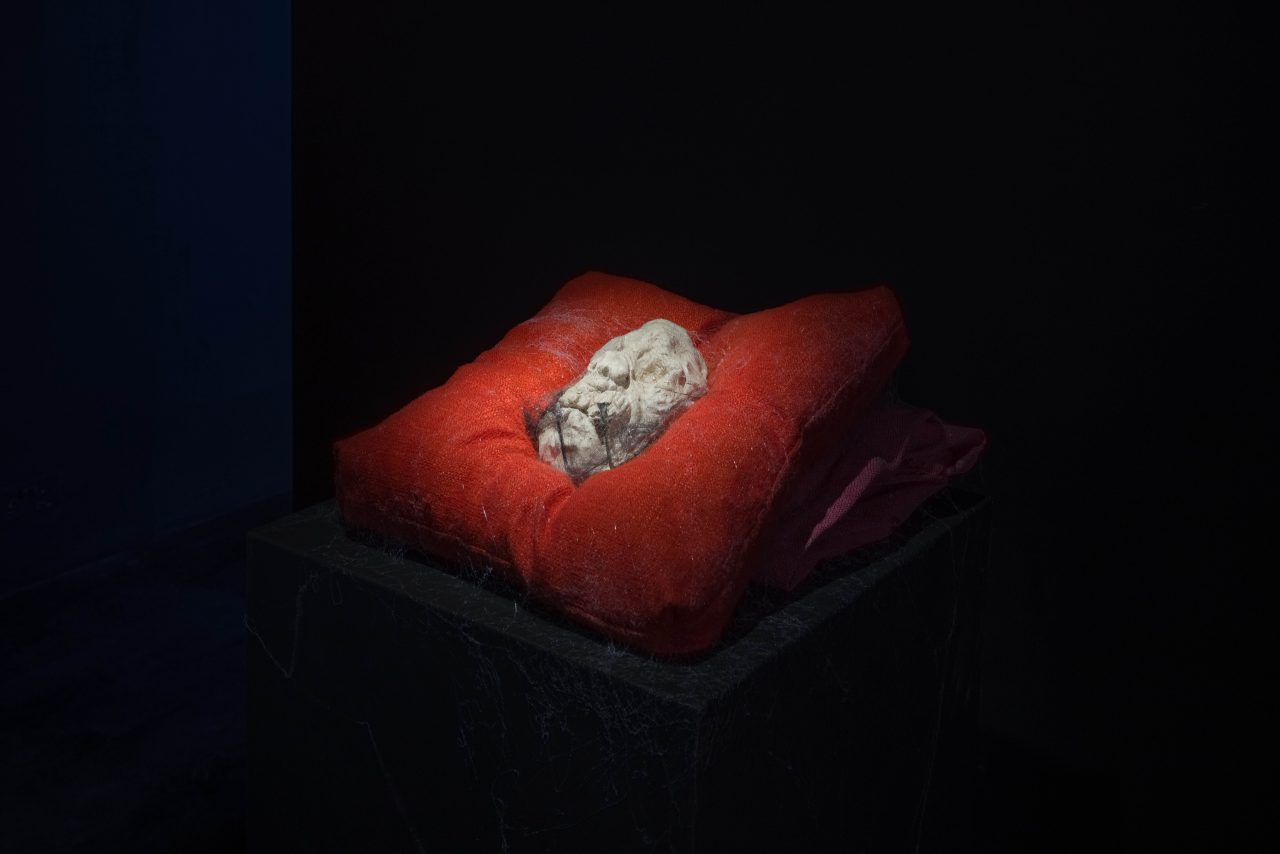

Richard Hawkins, The Garden of Loved Ones, March 23 – May 24, 2025, Empty Gallery, Hong Kong. Courtesy of the artist and Empty Gallery. Photography: Felix S.C. Wong.

Richard Hawkins, The Garden of Loved Ones, March 23 – May 24, 2025, Empty Gallery, Hong Kong. Courtesy of the artist and Empty Gallery. Photography: Felix S.C. Wong.

Richard Hawkins, The Garden of Loved Ones, March 23 – May 24, 2025, Empty Gallery, Hong Kong. Courtesy of the artist and Empty Gallery. Photography: Felix S.C. Wong.

Richard Hawkins, The Garden of Loved Ones, March 23 – May 24, 2025, Empty Gallery, Hong Kong. Courtesy of the artist and Empty Gallery. Photography: Felix S.C. Wong.

Richard Hawkins, The Garden of Loved Ones, March 23 – May 24, 2025, Empty Gallery, Hong Kong. Courtesy of the artist and Empty Gallery. Photography: Felix S.C. Wong.

Richard Hawkins, The Garden of Loved Ones, March 23 – May 24, 2025, Empty Gallery, Hong Kong. Courtesy of the artist and Empty Gallery. Photography: Felix S.C. Wong.

Richard Hawkins, The Garden of Loved Ones, March 23 – May 24, 2025, Empty Gallery, Hong Kong. Courtesy of the artist and Empty Gallery. Photography: Felix S.C. Wong.

Richard Hawkins, The Garden of Loved Ones, March 23 – May 24, 2025, Empty Gallery, Hong Kong. Courtesy of the artist and Empty Gallery. Photography: Felix S.C. Wong.

Richard Hawkins, The Garden of Loved Ones, March 23 – May 24, 2025, Empty Gallery, Hong Kong. Courtesy of the artist and Empty Gallery. Photography: Felix S.C. Wong.

Richard Hawkins, The Garden of Loved Ones, March 23 – May 24, 2025, Empty Gallery, Hong Kong. Courtesy of the artist and Empty Gallery. Photography: Felix S.C. Wong.

Richard Hawkins, The Garden of Loved Ones, March 23 – May 24, 2025, Empty Gallery, Hong Kong. Courtesy of the artist and Empty Gallery. Photography: Felix S.C. Wong.

Richard Hawkins, The Garden of Loved Ones, March 23 – May 24, 2025, Empty Gallery, Hong Kong. Courtesy of the artist and Empty Gallery. Photography: Felix S.C. Wong.

Richard Hawkins, The Garden of Loved Ones, March 23 – May 24, 2025, Empty Gallery, Hong Kong. Courtesy of the artist and Empty Gallery. Photography: Felix S.C. Wong.

Richard Hawkins, The Garden of Loved Ones, March 23 – May 24, 2025, Empty Gallery, Hong Kong. Courtesy of the artist and Empty Gallery. Photography: Felix S.C. Wong.

Richard Hawkins, The Garden of Loved Ones, March 23 – May 24, 2025, Empty Gallery, Hong Kong. Courtesy of the artist and Empty Gallery. Photography: Felix S.C. Wong.

Richard Hawkins, The Garden of Loved Ones, March 23 – May 24, 2025, Empty Gallery, Hong Kong. Courtesy of the artist and Empty Gallery. Photography: Felix S.C. Wong.

Richard Hawkins, The Garden of Loved Ones, March 23 – May 24, 2025, Empty Gallery, Hong Kong. Courtesy of the artist and Empty Gallery. Photography: Felix S.C. Wong.

Richard Hawkins, The Garden of Loved Ones, March 23 – May 24, 2025, Empty Gallery, Hong Kong. Courtesy of the artist and Empty Gallery. Photography: Felix S.C. Wong.

Richard Hawkins, The Garden of Loved Ones, March 23 – May 24, 2025, Empty Gallery, Hong Kong. Courtesy of the artist and Empty Gallery. Photography: Felix S.C. Wong.

Richard Hawkins, The Garden of Loved Ones, March 23 – May 24, 2025, Empty Gallery, Hong Kong. Courtesy of the artist and Empty Gallery. Photography: Felix S.C. Wong.

Empty Gallery is pleased to present The Garden of Loved Ones, the first solo exhibition by Los-Angeles based-artist Richard Hawkins in Greater Asia. Since emerging in the early 1990s, Hawkins has developed an idiosyncratic practice centered around the intense pleasure of looking and the dynamics of desire which animate both erotic and art historical expression. Employing collage as an underlying mode structuring his work in painting, sculpture, and various other media, Hawkins operates in that fertile and unobserved intersection between graverobber and archaeologist, fanboy and connoisseur, degenerate and avant-gardist. Treating his varied materials with equal measures of reverence and insouciance, he imbues dusty reproductions of Greco-roman statuary with the ardor of the teenagers gaze whilst subjecting images of male idols to a nearly philological rigor. Inducing us to look at these subjects anew, his work destabilizes received ideas of origin and influence—suggesting a queerer, more generous, and infinitely more promiscuous reading of art history.

For his show in Hong Kong, Hawkins stages a return to his long held obsession with the seminal figure of Tatsumi Hijikata (1928-1986), the enigmatic founder of Butoh dance*. Embodying many of the artist’s most cherished fixations—the aesthetic potential of the grotesque, an over regard for the male form, and a certain relationship to the occult—the ghost of Hijikata also comes to represent the concealed syncretism between east and west existing just below the surface of artistic modernism. A suite of new video works are inspired by, and presented alongside, a series of collages in the manner of Hijikata’s scrapbooks*. These bizarre and hermetic documents appropriate and disfigure now iconic fragments of the Western canon—Picasso, Redon, and Bellmer, amongst others—in order to translate them into choreographic instructions, contorting history in order to expand the ways in which we might contort our bodies and minds.

In his homage to these scrapbooks, Hawkins emphasizes the surreal juxtapositions, distortions of context, and interpretive perversity which fueled Hijikata’s radical transformation of movement. Pasted together upon a colored ground—he Ankoku collages are defined by asymmetric grids in which textual fragments, appropriated images, and scraps of kraft paper are arranged in rhythmic intervals of an incantatory character. Saturnine and yet seductive, these collages invite the viewer into a shared game of refined voyeurism, challenging them not only to identify the fragmented masterpieces within but also to partake of their perverse poetic logic—their fraught push-pull of associations and resonances. Rodin’s desolate bronzes morph into hungry ghosts, Klimt’s beguiling Danae receives a golden shower. In much the same way that the first flowering of modernism derived its artistic potency from selectively appropriated and misinterpreted fragments of the non-Western, Hawkins draws attention to the way in which Hijikata disfigures these Western bodies—in a very literal sense—chopping them up and rearranging them like a mad surgeon operating on so many dolls.

The figure of Hanako, whose recurring image haunts the exhibition almost as much as Hijikata’s own—is invested with a particular pathos*. Obsessed with depicting her anguished expression, Rodin made countless works based on Hanako but only ever depicted her as a disembodied head. Perhaps her very foreignness, her supposedly asiatic opacity, allowed her to function as a malleable surface which could mirror the artist’s deepest impulses. There is indeed a terror in this reduction of a unique existence to that of mere object or projection surface—and yet, as seen by Hijikata (who resurrects Hanako as an expressive tool in his dances), perhaps a paradoxical freedom as well—a liberation from the performative burden of self-identity. The nightmarish truly reveals itself in that moment when what we had naively assumed to be insensible matter rebels, and by doing so, reveals itself to be animated by an unfathomable inner principle.

In a series of new videos which accompany and expand the Ankoku collages, the screen itself functions as a charged mise-en-abyme through which images travel to interpret us. Within this space of haunted virtuality, the viewer is confronted with a quivering profusion of exhumed fragments—perfumed corpses scenting the gallery with their delirious odor; a Warburgian house of horrors. The interstices between artworks become animated by an eccentric sense of movement, sometimes transforming into one another through vaporous mutations, at other times convulsing as if in the throes of post-coital spasm. Outside the delimited boundary of the frame, we have the sense of an entropic void teeming with unnatural life, reproducing itself endlessly through a process akin to spontaneous generation. Threaded between the collages they reference, the overall effect of these films is vertiginous in Didi-Huberman’s sense—permeated with the overwhelming feeling that “the present is woven with multiple pasts” whose labyrinthine complexity exceeds our subjectivity.*

For a previous presentation of his Ankoku works, Hawkins chose the title Hijikata Twist. Evoking the contorted postures of butoh choreography, the gesture of twisting also implies the transmutation of a straight geometry into a complex topography. For Hawkins, desire for an image is already itself a (mis)translation or twisting—and it is this desire which underlies our perpetual groping towards self through the medium of the other. By channeling and perverting the method of Hijikata, the ensemble of works on view in The Garden of Loved Ones challenge a teleological understanding of art history—with its juvenile fixation on paternity, originality, and purity—dissolving the categorical priority of the Occident in the process. However, the staging of this ensemble of works in Asia looks past the current fashion of reparative wish fulfillment via substitution or addition to the canon to suggest a more radically generative potentiality. Conjuring the mutilated reflection of our own reified desires, these works suggest a path beyond the rigid performance of collective history through a privileging of individual fluidity and pleasure. In a city—Hong Kong—itself often imagined as mere container: a chimeric amalgamation of cultures defined by the phantasmic flows of global capital and the specter of colonialisms past and present, Garden suggests a possible détournement.

_

* Tatsumi Hijikata was the founder of Ankoku Butoh (meaning dance of darkness), widely known and practiced today as Butoh. Hijikata arrived in Tokyo from the rural Tohoku region in 1952 and worked blue-collar jobs to support his dance pursuits. As his rural accent set him apart from Tokyo’s urbanites, he filled his time reading French writers, such as Jean Genet, Antonin Artaud and Georges Bataille. Aesthetically, he looked towards artists such as Egon Schiele, Hans Bellmer and Willem De Kooning. Hijikata’s provocative performances stemmed from this exploration of eros, debauchery, disease and death, evoking the dark half of the human psyche.

* From the 1960s onwards, Hijikata created a series of Butoh no tame no sukurappubukku (Scrapbooks for Butoh), filling them with images culled from art books, newspaper clippings, photographs, and dance notations known as butoh-fu — developed by Hijikata as a methodical body of movement techniques.

* A geisha turned dancer who originally emigrated to Europe during the vogue for Japonisme, Hanako became a muse to Rodin. The artist produced more sculptures of her than almost any other figure during his artistic career.

* Georges Didi-Huberman, The Surviving Image: Phantoms of Time and Time of Phantoms : Aby Warburg’s History of Art (Penn State University Press, 2018).

Features:

7PM In Hong Kong, Geoffrey Mak, Spike Art Magazine, April 20, 2025

Slugs, AI, Ghosts: Richard Hawkins’s Haunted House, Bradford Nordeen, Frieze, May 14, 2025

Mentions:

Nine Solo Shows to See in Hong Kong, Spring 2025, Anna Dickie, Ocula, March 27, 2025

7 Shows to See During Hong Kong Art Week 2025, Claire Shiying Li, Frieze, March 25, 2025

The best shows to see in Hong Kong ahead of Art Basel, Payal Uttam, Art Basel, March 20, 2025

A pitch-black art gallery — now that’s a bright idea, Ophelia Lai, The Financial Times, March 19, 2025